Who gets to belong to the land? And Why?

Around the Table: Reweaving Belonging with Kristie Cabrera and Enrique Salmòn in conversation with Steph Lew

BY ADA CUADRADO-MEDINA

Our Around The Table series features informal conversations between food workers, thought leaders, elders, organizers, and creatives about emergent insights in food culture. Together, we sink our teeth into the juicy stories, live questions, and critical conversations buzzing in food and culture spaces.

How do we cultivate a deeper sense of belonging to land, food and the wild through the lens of Indigenous ecology and disability justice? What is possible when we reimagine a world where belonging means to care for the lands, waters and people that nourish us?

These were some of the questions that Food Culture Collective’s Network Weaver, Steph Lew, brought to the table on December 8, with disability justice advocate, Kristie Cabrera, and Indigenous ethnobotanist Dr. Enrique Salmón.

They were joined by over 60 guests around the virtual table for a juicy conversation that unearthed ways we can grow a food culture that centers accessibility and leaps courageously into the vibrant potential of the “gray spaces” that lie beyond extractive relationships to food and land.

From listening to our non-human kin and learning about growing food from folks with disabilities to exploring the power of language to subvert binary thinking and seed sharing as a love language—together they dug into ways we can stitch ourselves into relationships of mutual belonging.

Full recording of Around the Table: Reweaving Belonging with Kristie Cabrera and Enrique Salmón

What follows are some highlights and audio excerpts from this powerful conversation, as well as some thought-weaving. You can read and listen through the whole piece, or pick and choose based on the questions you’re most drawn to. This was a rich hour-long conversation and we encourage you to tune in to the entirety by watching the video embedded above.

Some quotes have been edited for length and clarity. To view the full, unedited transcript of the conversation with Kristie, Enrique, and Steph, click here. All graphic recording illustrations by Cori Lin.

Let’s set the table: What do you want to bring into this virtual conversation space?

We invite our conversation guests into the practice of setting the virtual table with an offering—a poem, song, photo, object, libation, ritual, prayer, breath—to share with the people in the space so that guests can show up in their wholeness and define the context for their conversation.

Kristie offered us an excerpt from Alexis Pauline Gumb's book, “Undrowned,” inviting us into the practice of listening—not just to humans— but across species to foster transformation. Enrique shared a story of his visit to Arnhem, in northern Australia where, as part of an Indigenous exchange program, he experienced getting to know the land, as well as the land getting to know him.

How can we expand our understanding of belonging?

Whether it’s with our communities, families, the land, or our non-human kin, Kristie and Enrique share how belonging can feel complex and unique across all of these relationships. Because our dominant culture is steeped in binary thinking, belonging can be hard to access for those of us who don’t neatly fit into pre-defined categories.

Digging deeper into how our understanding of “who gets to belong to the land”, Steph asked Kristie and Enrique to share experiences from their lives that opened up their understanding of who gets to belong and how.

Enrique called in the Indigenous character of the Trickster consciousness as a being that opens portals into the non-binary gray areas that are all around us. He brings us to an inter-tribal Powwow, where he recalls the expansive power of a Two-Spirit dancer in ceremony. Kristie shares how the ableist bias in mainstream culture limits our thinking about how to grow food, and what we might gain from including folks with disabilities in our food movements. Together they explore the question of what is possible when we seek knowledge and community with people who are excluded from dominant culture’s vision of who belongs in food spaces?

Art by Cori Lin

ENRIQUE: One of my favorite topics [is] trickster consciousness. And a lot of folks get this idea that Trickster is always just Coyote. You know, someone that causes problems and gets in trouble and so on. Or maybe in the Pacific Northwest, it's, you know, the character might be a raven. But, Trickster is more than just a troublemaker. In fact—I even have trouble with the word trickster—but it's now the word that we apply for this, this recognition among Indigenous communities around the world of that gray space that occupies everything around us, and that we, at the same time occupy and can see. And we know it's there, but it's hard to enter into it to fully— live within it.

Trickster helps us to see those other places that we know are there, but don't always recognize—and are sometimes prepared to see. And, in just about every Indigenous ceremony, there's going to be that recognition of that gray space. And, when I think about non-binary conditions, and thought, and beingness, I always think about that.

“[W]hen we seek knowledge from disabled people about growing food, we realize, Wow! There are so many different ways that we can receive gifts from the land. ”

KRISTIE: So, I would like to share just an overall awareness that I've gained over the years from working in disability justice, and how this has come up for me. And what I've learned is that nearly everything in our world, especially in the United States, was designed—after colonizers had come and invaded—for non-disabled people. That is because our history is ableist along with being racist and sexist and other things. And, this ableist society encourages us to think in a binary. Most of the time we don't even realize it. We just assume how things should be, because that's how we have always seen it done.

We can take growing food as an example. If you were to research how to grow food, you'll mostly find information from non-disabled people, who are farmers or are gardeners, and, find gardening and farming products that were designed by non-disabled people. If you were in a room with people who had growing food knowledge, most people would seek out people who aren't visibly disabled to receive information on growing practices. We all have this visual representation of who a farmer or gardener is in our mind. And, disabled people grow food! And, they have great practices, and they want to grow food. And, when we seek knowledge from disabled people about growing food, we realize, Wow! There are so many different ways that we can receive gifts from the land.

Disabled people have identified various ways to do this from intentionally selecting food that supports the places their body can access, like food that grows tall. Beans, squash and cucumbers—to focus on plant relationships— like using the three sisters of corn, bean, and squash, and other combinations to maximize small spaces in order to preserve energy. Those are just two examples. And, there's so much more out there, and, you know, my goal, unless somebody else wants to take it on, is to one day have the capacity to archive all this information, because there isn't a collection of it, and it's, great wisdom.

I started this project called Growing Food in this Body. But, you know these things take time and energy, so that's currently on pause. But, I'm still always, you know, looking out and listening to disabled people around me, and even embracing my neurodivergency when it comes to growing food. And I hope that's something that all of you are inspired to do as well after today.

Art by Cori Lin

ENRIQUE: My wife [and I] were just talking a little bit about Rachel Carson, and how in 1962, she warned the rest of society about the dangers of pesticides and herbicides and pollutants, in general… And, my wife asked me, what if back in 1962, we had listened to Rachel, and changed the way we grow food? What would it have looked like? And, my wife's good at that. She's always asking those questions.

And I was thinking, yeah, what if in 1962, we had stopped this industrial approach to growing our food, and actually listened to the early permaculturists and regenerative agriculturalists, and found ways to produce our food that actually worked with the lands where we are growing this food, as opposed to imposing these food systems on these lands? What if we had listened to folks who had different ways of envisioning how to grow food, and, and adopted some of those techniques?

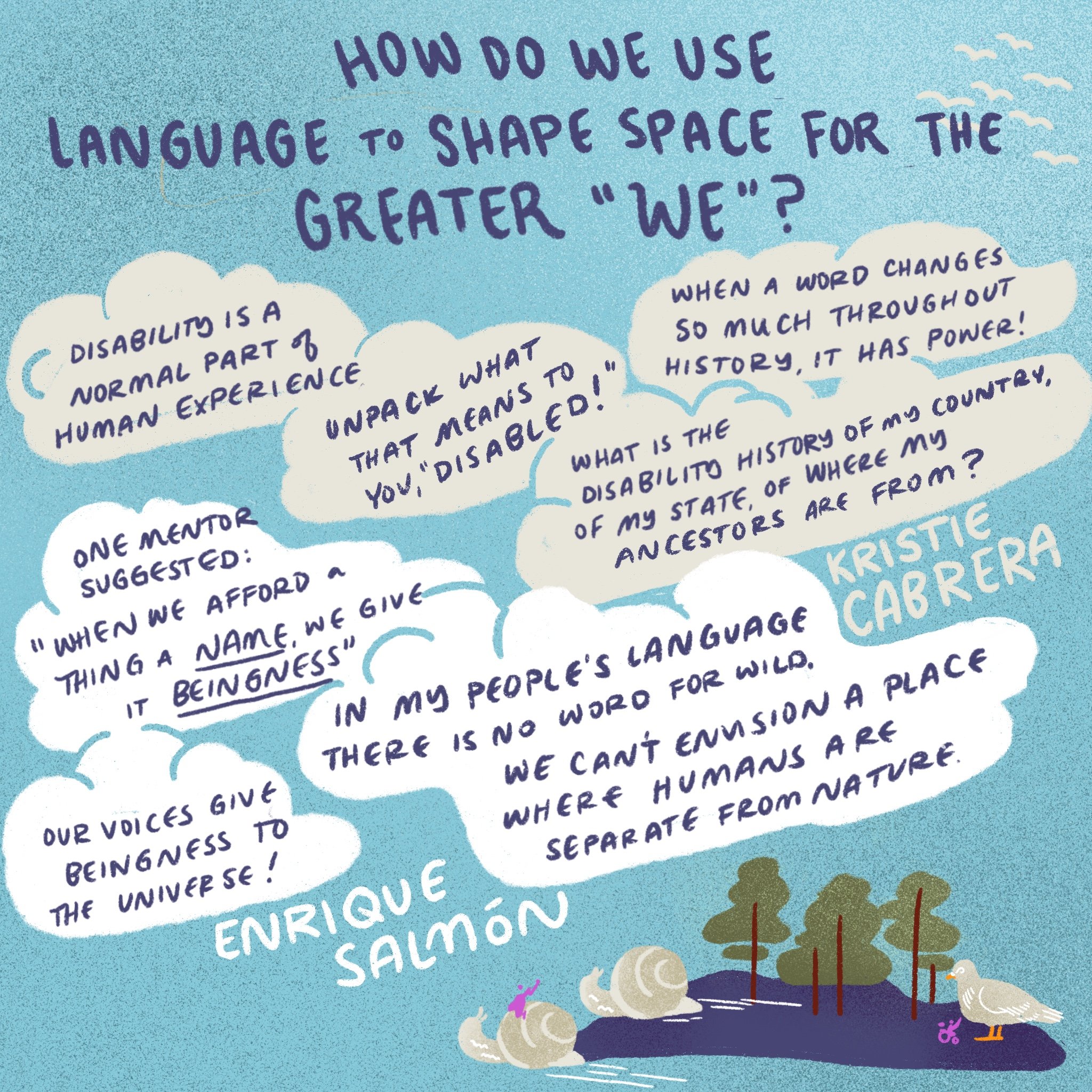

How have you approached language as a tool to create a bigger “we”?

Language is a powerful expression of culture. It can hold and shape our relationships with the world. Recognizing how words operate as tools, Steph prompted Kristie and Enrique to explore how language can be used to hold and create room for the “gray areas”—to be more inclusive of things that don’t fit neatly into predetermined boxes or categories.

Kristie introduced the term “pre-disabilty”— the idea that we will all likely experience disability during our lives—and took us on a deep dive into US disability history and how the word, “disabled” has been weaponized and the power of untangling what that word means to us. Enrique reflected on the power of words to give “beingness” to the universe and called up the Indigenous understanding of kincentricity—the idea that everything around us, from the birds to the trees, and the waters, are our relatives—as a way to redefine “the wild” to include humans in reciprocal relationship with the living systems we are part of.

Art by Cori Lin

KRISTIE: Language is so very important to disability justice, accessibility, and inclusivity work. And, my understanding of what it means to be disabled has evolved over time. I know now, that disability, that term we use to describe a certain group of people is not a bad word, and that people have been pushed to use other words, in order to avoid their discomfort, right? Special needs, differently-abled, diffability, everything else but disabled, because of the discomfort we have with variations of the human body and the mind.

And, now I know that disability is a natural part of human experience. It is normal. And disabled people are just as worthy as non-disabled people, so we don't have to cover that word up. I forgot the person who coined this term, but I also embrace the word pre-disabled. The idea that most of us are in this place where we may not be disabled now, but because disability is a part of the human experience, we will one day, be disabled. And, and that's okay.

ENRIQUE: Our words have energy. One of my mentors, Scott Momaday, once suggested that when we afford a thing a name, we give it beingness. And, that's because, when we speak, our voices are giving voice to the entire universe. We are the universe, and the universe only exists because we, as human beings, think about it and speak about it. And we sign about it. When we speak, it's the energy of the earth and the whole universe, giving beingness to things immediately around us.

I was once part of a group of authors who were brought together in Crested Butte, Colorado, for a retreat. And, the whole intention was, was for us to dialogue over the concept of wild and wilderness. And, afterwards we were to leave, and we had six or so months to write a chapter for this book. It's called, Wildness: Relations of People and Place. During the dialogue after, I was in the circle with everybody, and I finally said something that had been bothering me—Well, you know, in my people's language there's no word for wild. We can't, we can envision that concept of wilderness, of a place where humans are separate from the landscape itself. That's because for native peoples we are the land. The land is us.

We need to reconsider our words regarding our relationship to our places. Redefine what it means to be living in relationship with the place as opposed to continuing to use that word wild. Or maybe redefine wild so that the notion of wild or wilderness includes human beings. And, it's okay to leave more than just a footstep in the wilderness. You know, that's so alien to Native peoples— we gotta do more than just leave our footprints. We have to be a part of it. We have to engage with it. That means using the land, but using it in a sustainable way.

When has food sparked a sense of belonging for you?

Food cuts right to the heart of what we hold dear. It illuminates what we value, our relationships, our lived experiences—our cultures. From sharing heirloom seeds with neighbors as a love language and nurturing land that nurtures you, to honoring and supporting everyone’s relationship to food and nourishment regardless of ability, Kristie and Enrique shared experiences of belonging that were cultivated through their work with food.

ENRIQUE: We happen to have a new neighbor who moved in a month or so ago. She was outside watching what I was doing. And, they're immigrants from Taiwan. And, she was really interested in what I was doing. asking me, "You have a garden?"

I took her to the back to show her what I was doing, and then she held up her finger and she said, "Wait! Wait!" and she ran away and went to her house. She came back a little bit later with three different little jars of seeds. I didn't know what they were, and she couldn't explain to me what they were, but I realized they were—just by looking at them from experience—some kind of squash seed. I’d never seen any that were black like this. They look like big watermelon seeds, but almost a half-inch long.

I went ahead and planted them. And, it turns out I was planting loofah. And, I didn't realize that loofah is more than just something you let grow and dry and use in your bath and shower. That, when you pick 'em earlier when they're only, like, six inches long, you can eat them. And one of the other seeds was this huge, giant squash. It must've been a foot-and-a-half long and maybe about, you know, eight or nine inches wide—this big green striped, sorta thing. Looked like a light colored watermelon, but oblong shaped. And, it stretched for like twenty feet. This whole vine that stretched—that took up most of my front yard. But I think about that moment, because seeds, for me, are more than just something that I share, that I hope to plant next year. They represent hope. And in this case, they represent the expanding of my community.

So many people have a new neighbor, and are immediately, a little renascent, a little weary. But, in this case, through the seeds, we became life-long friends, and we belong to the same community of seedsavers. 'Cause now I give her some of my seeds that I've grown, of things I plant, like, you know, every year I save things like my Italian parsley. My wife is Italian, so I have to grow Italian parsley [chuckles] every year. But I share it with her, and she likes growing it and adding it to her dishes. Seed saving communities can go beyond just where you live. I have a friend, who, every year, from Colorado, sends me seeds that she gets from different Native communities. In this case, it was Yakima, a sweet yellow melon, which is incredible. And, through this act of [seed] saving and sharing, we can create even in an urban situation, a shared connection to a place.

“...Through this act of [seed] saving and sharing, we can create—even in an urban situation—a shared connection to a place. We can create an urbanized alternative; an alter-Native Indigenous-tude.”

KRISTIE: What I want to share is about my experience working in a school now, that aligns with my values. I work in a school for disabled children. Most of my kids use wheelchairs to varying degrees, and they use alternative forms of communication, so they can use an eye gaze device or communication boards to socialize.

Art by Cori Lin

And, my students eat—they love eating. And, our lunch period looks really different than probably most lunches that most people have seen. We have therapists, like myself, working with students on holding utensils, requesting water with their devices, on chewing skills. We have other students who receive nutrition through a G-tube—which is a tube that gets inserted from the outside of your stomach to the inside of your stomach—and allows nutrition to go directly into your stomach. So, they don't use their mouth for consuming food. And, what that means is that every single one of the kids have a unique relationship with food.

My job is to support this relationship, and that requires an understanding that food is important to human life. And, making sure that the amount of care I give myself when I'm eating, and when I'm eating with my loved ones, it's the same care I give to my students and their experience with food. What I often find is that non-disabled people who are supporting disabled people with eating, rush—force them to eat faster than necessary, because they want to get it over with. They don't check in with disabled people about how they want to spend their time in this dynamic together. They often avoid conversation or just talk at the disabled person, especially if that person is non-verbal. People make comments about how messy the disabled person or child is eating, about their saliva management. Then, once the food is done, it's just like whisked away, and there's not a moment to be thankful for the meal or check in.

If you're having a meal with your loved ones, what do you do after you eat? You sit back, you unbutton your pants, you sigh, you comment on how delicious it was. You say thanks for your company, for this food. Where is that sense of belonging, of co-occupation, of co-eating, this dynamic when we are treating, and working with and being in relationship with disabled people? If you’ve ever been to a nursing home, you might see this where people are really just rushing through that experience and making it seem like it's a burden.

Food can only create access to a sense of belonging if people have access to it. So, my goal is to create a collaborative space where my students can access their food. And, I'm bringing this energy of supportiveness and kindness. And, you know, I could go in a rant about how I wish supermarkets and farmers markets and farmers markets and farms that have CSA and people that create culinary products—I wish that they would understand the power they have, and how what they're doing is creating access for people to engage with their food. But, if it's not accessible, if it's not inclusive, right? How are people going to create a relationship with food that feels right for them?

Inverted Q&A: Do you have a question or invitation you'd like to offer folks?

We like to flip the traditional Q&A on its head, and invite our guests in conversation to offer up a question or invitation to the community that is tuning in. From feeling into a food future where connection to food and nature is radically accessible to all to leaning into our responsibilities to “everything and everyone around us” rather than just ourselves, Kristie and Enrique offer beautiful moments of reflection on belonging for us to carry forward.

There are so many more tasty bits to pull out from this energizing conversation, and so many more threads to follow. To watch the full Around The Table conversation, tune in to this video. You can also find the full transcript here.

We have so much gratitude for Kristie and Enrique—for the offerings of their time, wisdom, and invitations into action.To keep up with their work, be sure to follow them on social media at @hellokristielee and @iwigara. And be sure to subscribe to the Food Culture Collective newsletter to get first dibs on free tickets to our next Around The Table.

Check out some of the resources mentioned in this conversation!

Both Kristie and Enrique referenced various books, articles, and media throughout their hour-long conversation. We’ve gathered them here for your perusal.

Kristie:

Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals, by Alexis Pauline Gumbs

Growing Food in this Body: A Project to Dismantle Ableism Within Nature Spaces

Enrique: