What if we reimagined food culture by embracing our roles as future ancestors?

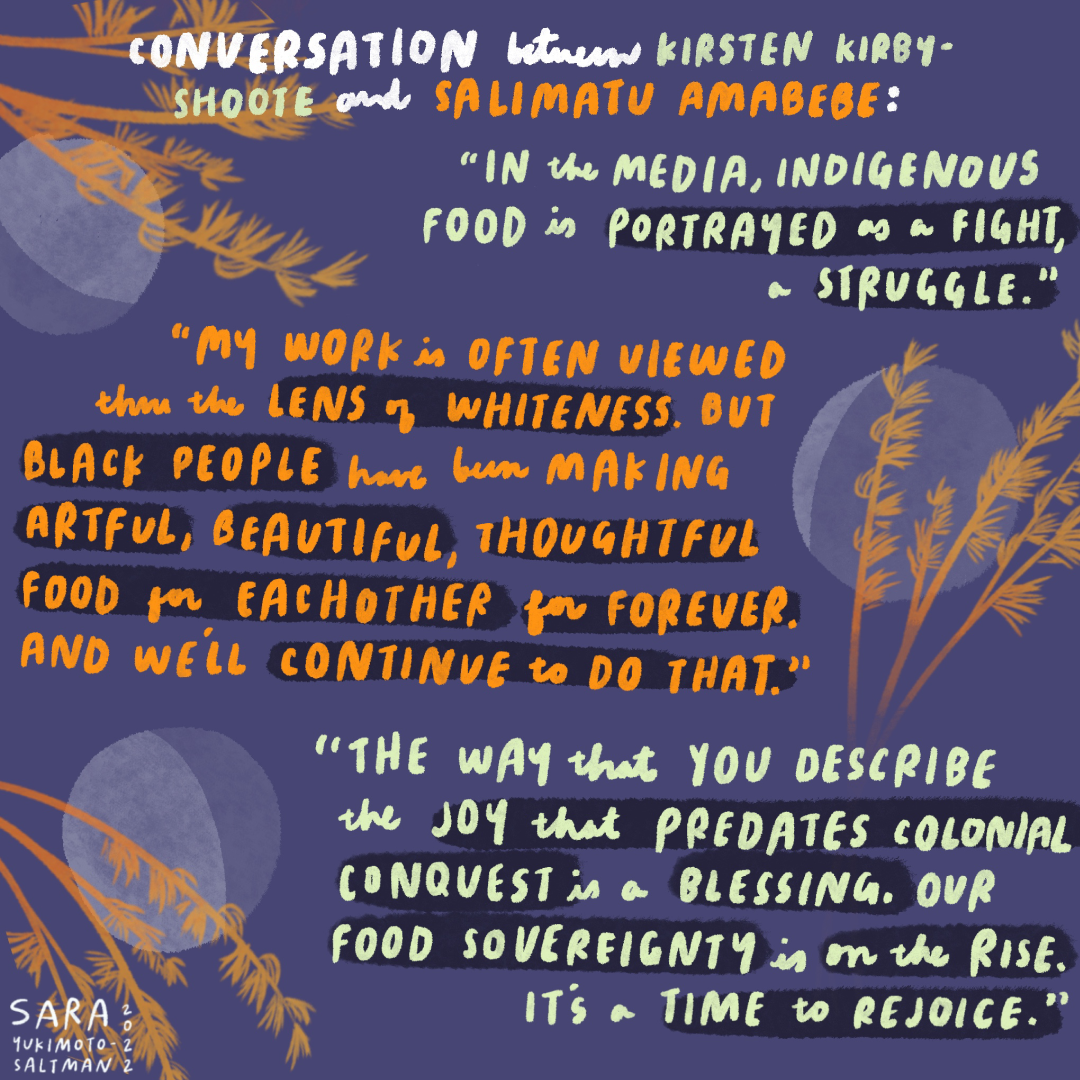

Around the Table: Nourishing Future Ancestors with Kirsten Kirby-Shoote and Salimatu Amabebe in Conversation with Shizue Roche Adachi

BY ADA CUADRADO-MEDINA

Our Around The Table series features informal conversations between food workers, thought leaders, elders, organizers, and creatives about emergent insights in food culture. Together, we sink our teeth into the juicy stories, live questions, and critical conversations buzzing in food and culture spaces.

What does it mean to be a future ancestor? What does it mean to feed a liberatory relationship to food, rooted in joy and care for ourselves and our future descendants? What can we learn by embracing both the joy and the fight in this work?

These were some of the questions that Food Culture Collective’s Narrative Strategist, Shizue Roche Adachi, brought to the table on June 28th, with Tlingit food activist, chef, and urban farmer Kirsten Kirby-Shoote of i-collective, and Nigerian-American chef and multimedia artist, and founder of Black Feast, Salimatu Amabebe. They were joined by over 60 guests around the virtual table for a deeply invigorating and insightful conversation about how embracing our roles as ancestors to future descendants can help cultivate a boldly reimagined food culture right now.

From subverting colonial logic to exploring what it looks like to honor and care for our ancestors, ourselves, and generations yet to come—together, they dug into navigating the ‘sharp edges’ of food work, celebration as resistance and reclamation, and how growing, cooking and gathering around food can transform our relationships to place and community across generations.

What follows are some highlights and audio excerpts from this powerful conversation, as well as some thought-weaving. You can read and listen through the whole piece, or pick and choose based on the questions you’re most drawn to. This was a rich hour-long conversation and we encourage you to tune in to the entirety by watching the video embedded below.

Some quotes have been edited for length and clarity. To view the full, unedited transcript of the conversation with Kirby, Salimatu, and Shizue, click here. All graphic recording illustrations by Sara Yukimo-Saltman.

Let’s set the table: Who are the ancestors you’re calling into this space?

We kick off all of our virtual conversations by inviting guests to ‘set the table’ with an offering or by naming something that they’re bringing into the space with them. This practice helps guests set their own contexts and helps us to be fully present in our bodies together. Gathering everyone around the table, Shizue invited Kirby and Salimatu to share which ancestors they wanted to bring into the space with us.

Kirby offered us a way to connect to our non-human ancestors all around us outside our screens and our windows, while Salimatu shared the deep family roots of their name, which means, “Peace be with you, voice of the people,” and a reflection on their “soul plant”—bitter leaf.

What does it mean to be a future ancestor?

To help ground the conversation, Shizue invited both Kirby and Salimatu to share their takes on what it means to embrace the role of “future ancestor.”

Both Kirby and Salimatu situated themselves as descendants of those who came before, naming a deep gratitude for the gifts they’ve received from their ancestors. From paths to healing generational trauma with the land, to an embodied relationship with care, food, and a sense of self—they remind us that utilizing those gifts and carrying them forward to our descendants is our responsibility as future ancestors.

Kirby: For me being a future ancestor…it's so reliant on the past ancestors and the knowledge that they've gifted to us. And all that knowledge is care, honestly. From growing our own food, to the methods on how to prepare that food, how to sit down on a table with your family, with your relatives. Give thanks to all the different components that made that meal.

From the soil who gifted you the nutrients to grow that plant, to the water that's provided life to future ancestors and nourishing them—it's about coming to terms with power intertwined with our land. And it's a painful relationship sometimes, and there's been a lot of trauma that's gone on, mostly at the hands of colonialism in this country…we all have our stories about how we have trauma with the land. And so for me, it's trying to heal that trauma for future generations. That's my work right now. I'm not there by any means. But it's going.

Salimatu: For me, there is just an understanding of where I come from and who I come from. My future is both written and unwritten. There is a trajectory that I will follow because of where I come, because of who I come from, and what our relationship is to care, and to food, and to our bodies, and our responsibility to each other into our communities. And to me— that responsibility—that's what I think about nourishing future ancestors. This responsibility that we have to the people who are coming after us, and to utilize those gifts from the people that came before us.

When did you realize the kind of nourishment you wanted to create for others?

Whether it’s pop-up experiences or stewarding the land, both Kirby and Salimatu work in spaces that revolve around feeding people in community.

Noting how their work goes far beyond the simple act of sustenance, Shizue invited them to each share a story about a time when they realized what kind of nourishment and care they wanted to offer their communities.

Salimatu shared how Black Feast was born from their journey to understanding that food and art could be expressions of care for their community. Kirby reminisced on how coming to Detroit opened the door to stewarding community experiences of joy, and beauty in their food—from lips glossed by smoked salmon, and the company of plant relatives at shared meals, to rejoicing in food sovereignty on the rise.

Salimatu: For me, I think that moving through the food world, the art world—and seeing those things as really separate—rather than understanding that the things that were important to me are care. In providing service and doing something that I feel a sense of purpose in. And so that's kind of how Black Feast came to be—because it is this merging of food and art. It's all the things that I care about, and we're not trying to make it exclusive. We're trying to make it for as many people as possible, and nourishing for as many people, and something that is really caring for community.

Kirby: There was a component of struggle to it, struggling and using food as a way to attain a different goal within food and growing food. Once I came out here to Detroit, I found freedom in that. And so my journey has been mostly about letting my people know how beautiful their food is.

What are the futurist practices you’re seeding in your work?

Often, when we talk about ancestors and traditions, there is a tendency to lean on a romanticized notion of “going backwards”, tied to the past. But being a future ancestor is about the here and now, and what we’re offering to the generations that come after us.

Pulling on this thread, Shizue asked Kirby and Salimatu to share the futurist practices they're seeding in their work.

Whether it’s through land stewardship as an act of collaboration across generations between human and non-human ancestors, or community dinners and celebrations as expressions of the gifts from our ancestors—Kirby and Salimatu see their work as part of stories much larger than themselves.

Kirby: I want everybody to know that, like, this work ain’t just me. I'm such a small fraction of all of the work that goes into creating a food system for our people and creating sovereignty for our people. You know there are elders doing more work than my 29 year old ass. Even the land is so much more of a player in the scheme of things, than I am. And that also needs to be recognized when there is any conversation about food. We’re instrumental in changing the narrative. But a lot of the credit goes to other relatives that aren't human relatives.

Salimatu: I really agree with Kirby in that I see myself as a very small aspect of this. I think that Black Feast was really created out of a need, and at a certain time in place. Had I not been in Portland, Oregon at the time, I don't know that it would have. It makes sense that it originated there because it felt so necessary, living in that place.

Now I want it to be something that will continue to grow and exist beyond me. And so that's something that I keep in mind with how we're doing things. It can never really be just about, like, “Oh, this is Chef Salimatu’s food.” It's not my project. It's just that I'm a part of it.

How do you relate to healing in your work?

In popular food media, when BIPOC folx in food work are platformed, we often see our work framed through a white lens—one that emphasizes experiences of trauma or pain rather than celebration or joy.

Noting how difficult it is to talk about nourishment without naming healing and how food is entangled in grief, Shizue invited Salimatu and Kirby to explore their experiences with healing in their work.

Salimatu: A lot of the early response I got from doing Black Feast was that it was a “healing space”. Or that it was a space where we were “really digging into racism.”

And I was like, “No! This is dinner for Black people. We're just celebrating Black artists, and having, like, a beautiful 4-course meal, and making it free or by donation for Black folks.” We're not trying to heal racial trauma. And also why the fuck should we be responsible for healing racial trauma? Like…we didn't do it! I think that there's the sense that I have, which is that they're often viewed through the lens of whiteness—like this work feels like so “necessary” rather than like, Black people have been gathering, and like eating and sharing food in community forever. You know, that's a part of what we do.

Kirby: The places within food that I've found the most healing is, like, in the… It's not even in traditional food. Honestly it's like you know, making fry bread with my friends in a huge kitchen! You know, you got a bunch of oil, and just cook for the whole fam. And that's still very real and valid, even though there's a lot of people who be like, “Aren't you supposed to be undoing the effects of colonialism?”

But it's more about how we interact with our community, and less about the actual food itself. It's a huge component, especially for me. But yeah, more about whatever happens during those dinners. You know all the ideas and all the creations we have. You know it's about that. Joy is gonna find a way—it always has and it always will.

How do you navigate the ‘sharp edges’ in your work?

From casting healing as “soft and gentle” to expecting BIPOC folx to be representatives of their entire lineage or communities—the policing of what healing and authenticity “should” look like causes serious tensions and frustrations around naming food spaces as ‘healing.’

Shizue invited Kirby and Salimatu to talk more about navigating the “sharp edges” in their work.

Kirby: I'll defend any Black or Brown person’s anger towards the system. I'll help somebody light something on fire. I think that rage is expressed through a lot of means. And it's not always bad to have aggression and to be able to express that through food and through feeding people.

Part of that drive and part of that anger is why I do my work, but it's also through love. But, when somebody you love gets hurt, for me, my first resort is anger. So it's kind of that fire. It’s the feathers that push the air towards the fire…and make it consume everything.

Salimatu: I feel like talking about anger in the work that we're doing is really important. Anger is not equal to violence—those are two separate things. We've learned to equate anger to violence. A big part of what Black Feast is—I'm making culinary interpretations of artists' work. And so a lot of these Black artists’ work is around anger. So when I'm creating those dishes, it's around, okay—what does anger taste like? What does anger feel like, you know? Is this something that is comforting or soothing? Or is it something mirroring that response? And how that goes into the call of the work.

And the other thing that I also wanted to talk about is what you have mentioned around making fry bread, and how there is this pressure to, oftentimes, be “authentic” through a white lens. But also, I'm a chef and an artist and I'm constantly taking things from my surroundings and learning new things, and wanting to express those through food. And how through the lens of colonialism, there's this pressure on Black and Brown folks to be like the representatives of our entire lineage.

We're carrying things with us, and also we're creators and we're creating new things, and we're allowed to make new shit! And we're allowed to do things that are fun and different, and create new recipes that we can hand down to the future generations, and how it's important to allow for that.

Kirby: I think the purity of having to be completely “decolonized” is an unfair pressure. And to have no creativity expended to you, no room for your brilliance and like, your artistic drive, keeps us further from innovating and creating.

So yeah…we can't live in the pre-colonized state right now. We can work towards it—but that pressure in itself is only gonna hold us back.

What’s a question or thought you’d like people to continue chewing on?

To wrap-up their conversation in a space of wonder, Shizue turned the traditional Q&A on its head and opened space for Kirby and Salimatu to offer some questions for people to continue to sit with in the coming days and weeks.

Salimatu: I would like to leave folks with a practice that I've been doing, which I think is maybe a little bit cheesy. But I actually really enjoy the cheesiness of it. Being a parent to myself. Being my own ancestor. So I have a lot of conversations with myself, and like when I do something, like when I fuck up I'm just like, “Hey Salimatu, it’s okay, like, I still love you.” So it can be like a cheesy practice, but I really encourage everyone to just like, spend, like a day, just being your own parent, and see all the moments in which you might think to abandon yourself. You know, when someone asks if they can get a rush deadline and you're thinking about like you know, not sleeping or like not taking care of yourself or skipping breakfast or something so you can do something for someone else or on someone else's timeline, and just like remembering kind of like just being a kid and just being like, “No, go to bed. No, you gotta have breakfast. Did you drink water today? How are you doing?”

And yeah, just really show up for yourself in a way where you feel responsible for yourself and you feel that you want to be your own parent. Be kind to yourself, and be gentle and forgiving.

There are so many more juicy bits to pull out from this nourishing conversation, and so many more threads to follow. To watch the full Around The Table conversation, tune in to the embedded video. You can also find the full transcript here.

We have so much gratitude for Kirby and Salimatu—for the offerings of their time, wisdom, and invitations into action.To keep up with their work, be sure to follow them on social media at @_challahgram and @salimatuamabebe. And be sure to subscribe to the Food Culture Collective newsletter to get first dibs on free tickets to our next Around The Table.